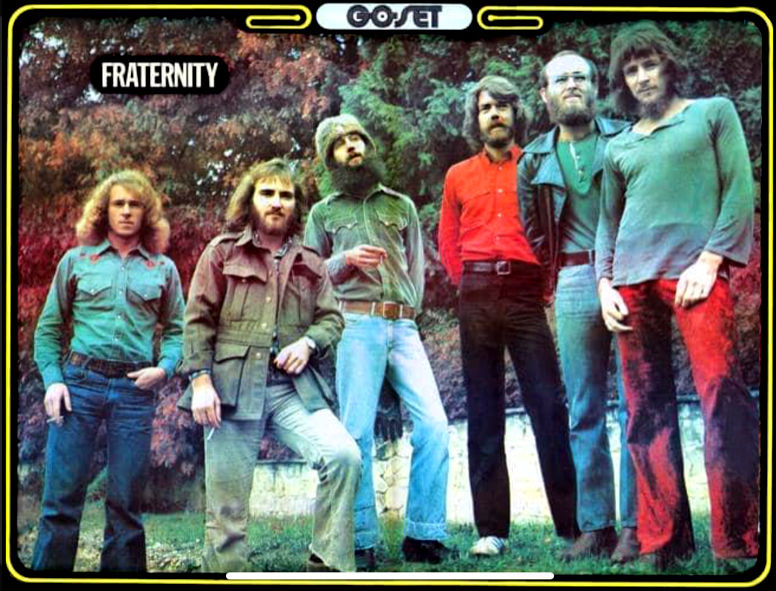

Adelaide was probably the last place Ronald ‘Bon’ Scott would have expected to end up, but within six months of the Valentines’ 1970 dissolution, it was there that he found himself, living the whole communal hippie trip as a member of the band Fraternity. Leader Bruce Howe asked Bon to come up to Sydney to join his band as soon as he heard the Valentines were breaking up. Bon leapt at the chance: Fraternity was the hottest new band in the land.

Adelaide was probably the last place Ronald ‘Bon’ Scott would have expected to end up, but within six months of the Valentines’ 1970 dissolution, it was there that he found himself, living the whole communal hippie trip as a member of the band Fraternity. Leader Bruce Howe asked Bon to come up to Sydney to join his band as soon as he heard the Valentines were breaking up. Bon leapt at the chance: Fraternity was the hottest new band in the land.

Fraternity had strong Adelaide connections to begin with. It was, after all, the band that had spun off the hallowed Levi Smith Clefs, an Australian musical institution led by Adelaide legend Barrie McAskill. Bruce Howe himself was an Adelaide boy, as was drummer John Freeman. And the band was already tied to Adelaide-based independent records company Sweet Peach.

The Levi Smith Clefs had visited Adelaide in June 1969 to play a season at the 20 Plus Club. Sweet Peach put them into the studio at that time; after a matter of mere hours, they emerged with a finished album. At around the same time, Doug Ashdown, a folkie who had recorded for CBS in the sixties was back in hometown Adelaide at a loose end. Joining forces with Jimmy Stewart, he set to work on an album for Sweet Peach, for which taking a leaf out of Dylan’s book, the Clefs was recruited ‘to provide some rhythm’.

The Clefs’ album, Empty Monkey, was released in March 1970. Complete with a laminated, stiff-card gatefold sleeve and esoteric artwork, it looked for all the world like an American record. Appropriately, it was greeted with unbridled weal. Go-Set’s review opened with the line “THIS IS THE BEST ROCK ALBUM EVER PRODUCED IN AUSTRALIA”.

In retrospect, Empty Monkey is ponderous and overwrought, but at the time, it was groundbreaking simply because it was an album, and so few other Australian bands had actually cut albums. Meantime, MCA in America had heard the Doug Ashdown album – a double-set no less (Australia’s first) called Age of Mouse – and expressed interest in releasing it. All this went to the Clefs’ heads. Didn’t backing Australia’s answer to Dylan on a double-album make them the Australian equivalent of the Band?

The Clefs became convinced they were leading Australian rock’s charge into a new age of seriousness, so they split from Barrie McAskill. Christening themselves Fraternity, they headed for Sydney, leaving McAskill high and dry in Melbourne. They set up house in a two-storey terrace in Jersey Road, Paddington and Sweet Peach put them straight into the studio to cut a single to capitalise on the radio ban (on British and most Australian recordings, over copyright dispute).

With two tracks in the can – one a Doug Ashdown song Why Did It Have To Be Me?, the other a Moody Blues album track, Question – Fraternity signed on with the dominant Nova agency to look for work. The Valentines’ decision to break up had been announced by then, and so Bruce got in touch with Bon. But even before Bon could make it up to Sydney, Fraternity scored the resident spot at Jonathans, a disco on Broadway in south central Sydney. Junior partner in the residency was a young band from the Sydney suburbs called Sherbet.

With two tracks in the can – one a Doug Ashdown song Why Did It Have To Be Me?, the other a Moody Blues album track, Question – Fraternity signed on with the dominant Nova agency to look for work. The Valentines’ decision to break up had been announced by then, and so Bruce got in touch with Bon. But even before Bon could make it up to Sydney, Fraternity scored the resident spot at Jonathans, a disco on Broadway in south central Sydney. Junior partner in the residency was a young band from the Sydney suburbs called Sherbet.

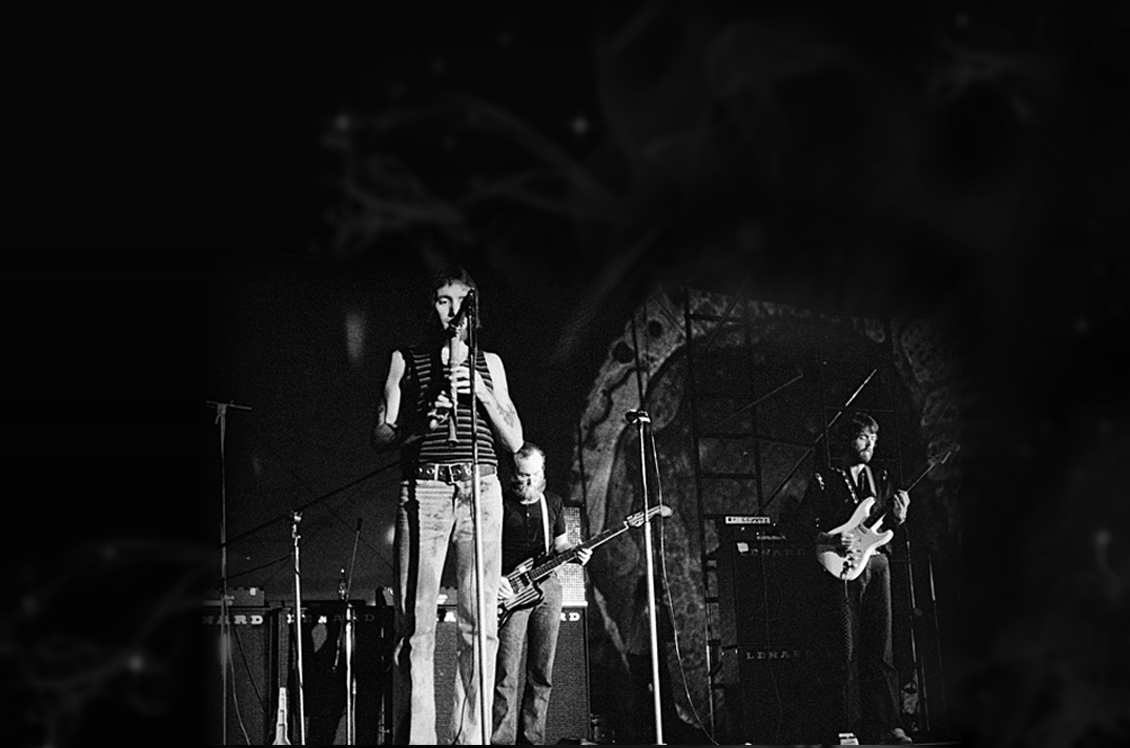

With Bruce and John Bisset sharing singing duties as they had on the single, the band played Doug Ashdown songs, Band songs, a few songs left over from the Clefs, and a few standards like Little Queenie. Other musicians would sit in, among them Maori vocalist extraordinaire Leo de Castro, ‘Uncle’ John Ayers a harmonica player who regularly sat with Copperwine, and a singer by the name of Dennis Laughlin, who had recently left Sherbet to be replaced by Daryl Braithwaite. Fraternity was promising the arrival of a great new singer.

Meanwhile, in Melbourne, as Barrie McAskilll assembled yet another Clefs, Bon played the last few Valentines shows. By the time he arrived in Sydney, he has sprouted a goblin-like beard. He slotted straight in. “The last time we saw Bon Scott was at a teeny-bopper concert in Melbourne, with the Valentines,” read one Sydney paper. “We thought he was wasting his voice then. We know he was now. A distinctive heavy voice… and the group is very, very professional.”

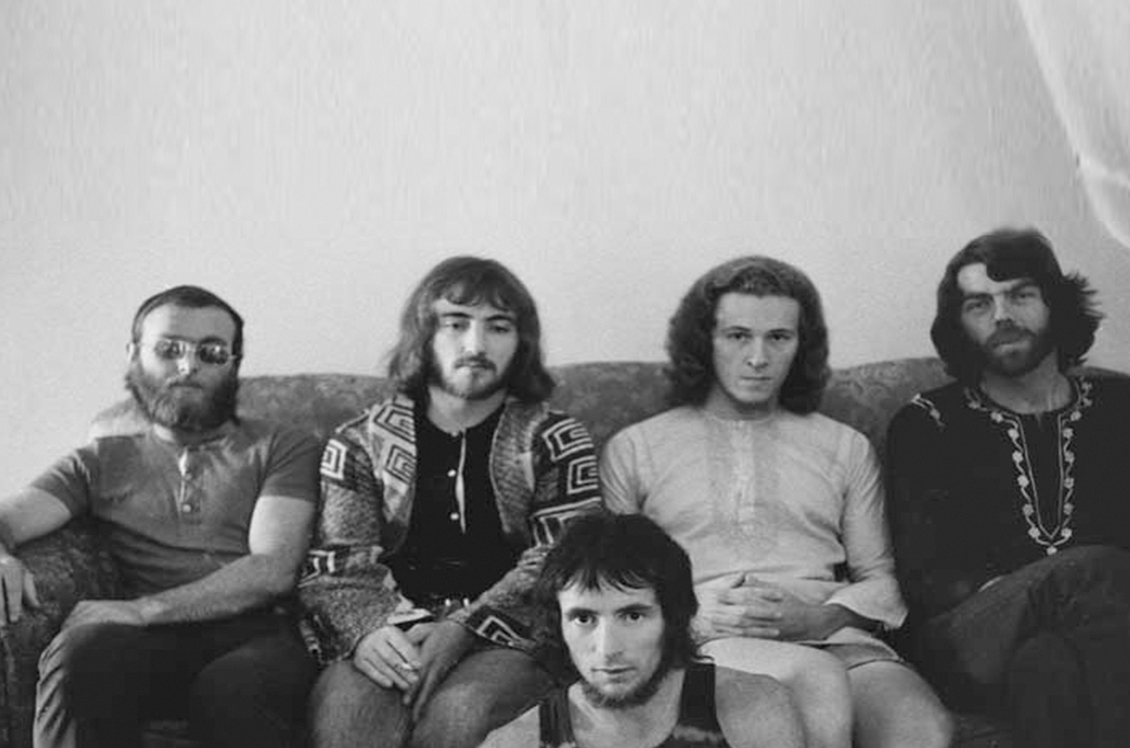

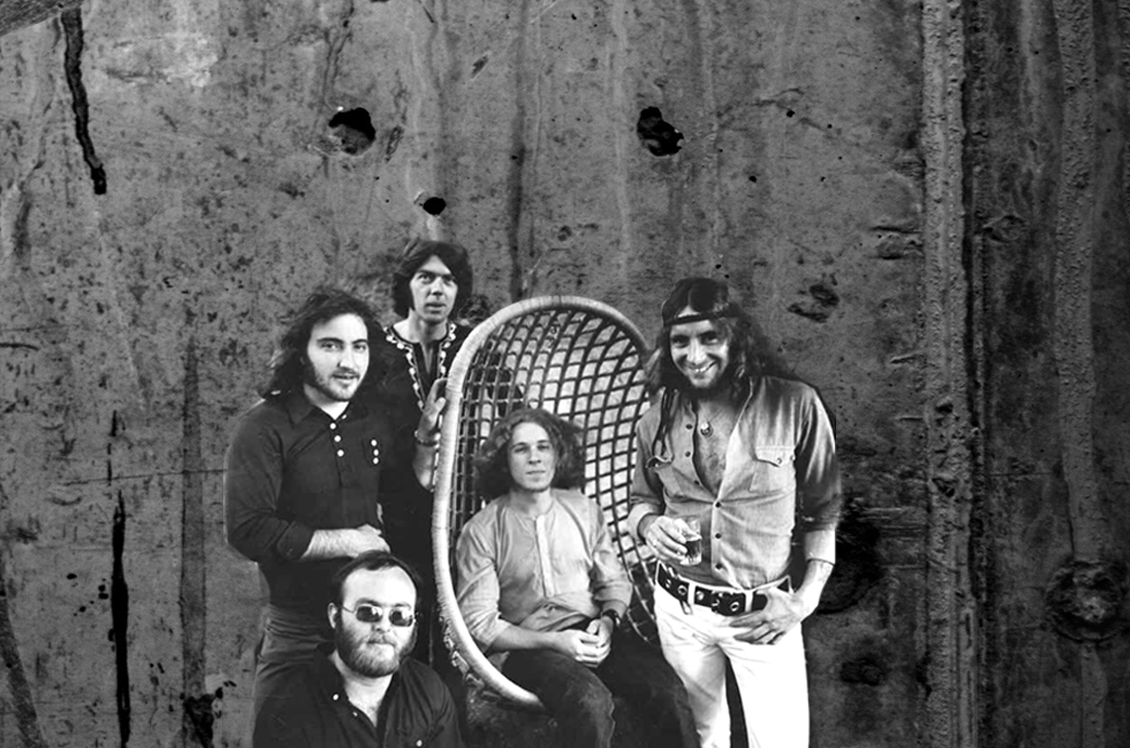

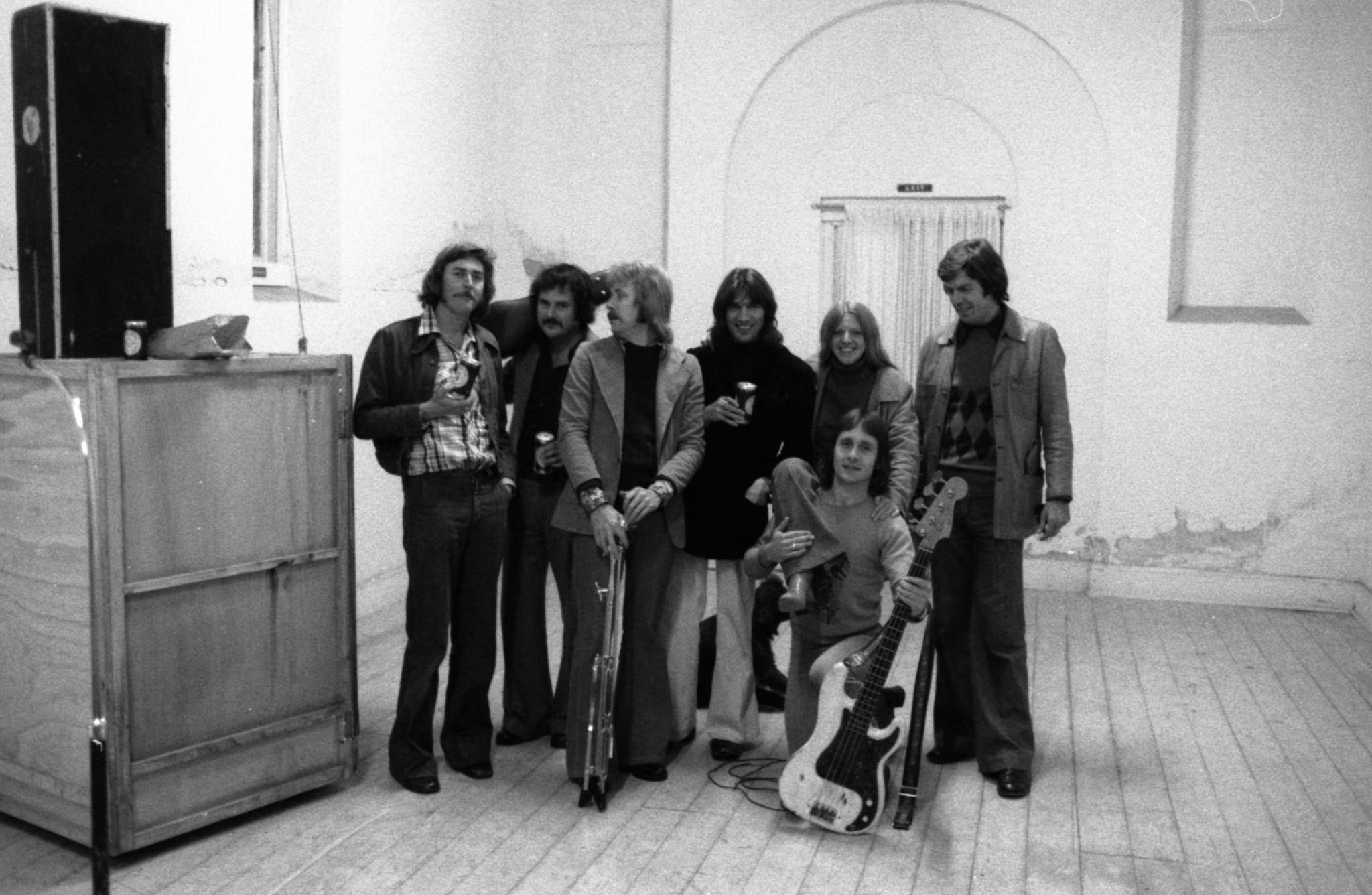

Fraternity was hot. The band boasted that MCA in America, after hearing the single, now wanted an album from them. Sweet Peach started hustling studio time. The Sydney Sunday Mirror ran a full-page pin-up of them, proclaiming them as “rapidly on the way to becoming Australia’s greatest hard rock group.”

Woodstock’s effect had been felt. The sheer musical naivety of the sixties had been outgrown. As far back as 1968, Australian musicians had begun searching for something – a sense of where the music had come from, so as to know where it might now go. When the radio ban was lifted after six months in October 1970, a new mood dawned. “It was an explosion of creativity, not all of it for the best, but everyone was having a go, trying to forge a new path,” said Sam See, a founding member of Sherbet, who would go on to join the Flying Circus, and then later Fraternity, and then later still, rejoin the Circus.

“I got to know Fraternity by being a late-night drinker at the Whiskey. The thing I really like about them was that they were trying to approach an Australian sound. Later on it happened. They weren’t really popular, but musicians, the hip cognoscenti, liked them. We would have heated arguments at Jersey Road – Bruce and I used to argue at great length and great volume – where I’d say, ‘Well, we blew you guys off stage tonight in terms of the audience,’ and he’d say, ‘Yeah but we’re doing something of our own.’

“’There were a lot of folk singers around then too, and so we all got into songs, words that meant something,’ said Peter Head, who had much in common with Fraternity as a member of Adelaide allies, Headbang. ‘It was the first time anyone used Australian place names in songs. I remember having arguments with people who said ‘you can’t use Australian names in a song they sound daggy, they’ve got to be American’.”

When Barrie McAskill and a new Levi Smith Clefs arrived back in Sydney to resume their Whiskey gig, Bruce Howe immediately swooped on them to poach drummer John Freeman, another old Adelaide boy, to replace Tony Buettel. When Bon moved into Jersey Road, the first thing he did, again, was paint his room fire-engine red. The house was a regular meeting place. Sam See lived just around the corner. Virtuoso Blackfeather guitarist John Robinson often slept on the couch. Robinson had almost completed a song called Seasons of Change which Fraternity helped him finish, so he gave it to them.

When Barrie McAskill and a new Levi Smith Clefs arrived back in Sydney to resume their Whiskey gig, Bruce Howe immediately swooped on them to poach drummer John Freeman, another old Adelaide boy, to replace Tony Buettel. When Bon moved into Jersey Road, the first thing he did, again, was paint his room fire-engine red. The house was a regular meeting place. Sam See lived just around the corner. Virtuoso Blackfeather guitarist John Robinson often slept on the couch. Robinson had almost completed a song called Seasons of Change which Fraternity helped him finish, so he gave it to them.

The turntable hit in the house was the recently-released debut album, In The Court Of The Crimson King by Robert Fripp’s prototype English artrock outfit King Crimson. Bon would sit cross-legged on the floor in front of the stereo, stoned, soaking it up. Other favourites Deep Purple, Procol Harum (Whiter Shade Of Pale had been a hugely influential record), Pocom the Band, Rod Stewart and Van Morisson. Mick Jurd was the band’s resident musicologist, and he named artists like Wes Montgomery, Barney Kessel and BB Kings as his heroes. The mood of the times was such that the more esoteric your taste, the more ‘progressive’ you must be.

Fraternity were trying to get a start on recording the album the Americans apparently wanted. The single had failed to do any business. By then though, the band was able to do any business. By then though, the band was able to fob it off as a premature and already redundant artifact. They were only thinking about the album. But the single was never released in America, and the album they would eventually finish, after a few false starts, would be shelved even in Australia.

Livestock, as the album was called when it was finally released by Sweet Peach over a year later, was a mishmash. Often featuring Bon on record, songs like Jupiter’s Landscape, Raglan’s Folly, You Have A God and It were pompous, ponderous pieces of artrock; Grand Canyon Suite was would-be Aaron Copeland; only the title track, Sommerville and Cool Spot still stand up as tight, sharp little exercises in sophisticated songwritting and arrangement. Fraternity appeared live on super-groovy new ABC-TV shot GTK. New national magazine Sound Blast put Bon on the cover, wearing war-paint and expression to match.

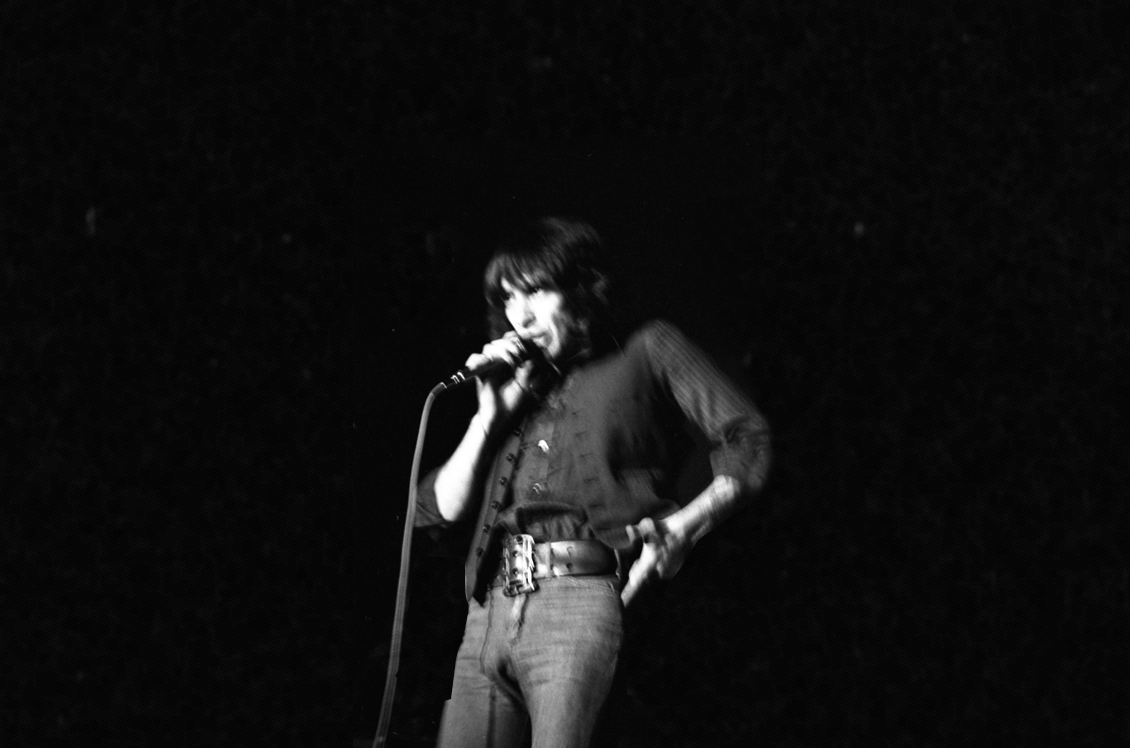

After playing a few shows late in September on the belated Australian tour by the 1910 Fruitgum Company, the band played the support spot on a tour by Jerry Lee Lewis and the Cuff Links. They “did some nice instrumental things,” Greg Quill reported in Go-Set,” and Bon, all painted and cheeky, managed to make people laugh a little.”

The Killer tour took Fraternity to Adelaide, where they supported Lewis at the Apollo Stadium, and played a couple of gigs of their own at a disco called Headquarters. It was this visit which would after the course of their career. Anticipation surrounding Fraternity naturally ran high in Adelaide. It was further pumped up because Vince Lovegrove, Bon’s co-lead vocalist in the Valentines, ironically, had also landed in Adelaide, and was in a position to hype his old mate’s new brand vigorously.

After playing a few shows late in September on the belated Australian tour by the 1910 Fruitgum Company, the band played the support spot on a tour by Jerry Lee Lewis and the Cuff Links. They “did some nice instrumental things,” Greg Quill reported in Go-Set,” and Bon, all painted and cheeky, managed to make people laugh a little.”

The Killer tour took Fraternity to Adelaide, where they supported Lewis at the Apollo Stadium, and played a couple of gigs of their own at a disco called Headquarters. It was this visit which would after the course of their career. Anticipation surrounding Fraternity naturally ran high in Adelaide. It was further pumped up because Vince Lovegrove, Bon’s co-lead vocalist in the Valentines, ironically, had also landed in Adelaide, and was in a position to hype his old mate’s new brand vigorously.

In addition to his gig as Go-Set’s Adelaide correspondent, Vince was writing a music column for the News, and had managed to get a local TV show up and running on Channel 9. The show, called Move like his newspaper column, was essentially an expanded, weekly variation of GTK. Its premiere episode of October 17 featured Fraternity, Australia’s only group with a completely original repertoire.

“They came – they played – they CONQUERED!” Vince wrote in Go-Set of the headquarters gig. Never ad prodigal sons been made to feel for more welcome. But if the band had been progressing quite nicely, the course of its career was about to alter with the intervention of one Hamish Henry. He was the man behind the Grape Organisation, a booking agency that promoted Headquarters, among other Adelaide gigs. But Hamish Henry was much, much more than the average rock entrepreneur.

Henry was a rich kid with a vision, a patron of the art who had been swept up in the euphoria of the Age of Aquarius. Born into old Adelaide money, he held down a day job with the family business, State City Motors, whilst he also ran a successful North Adelaide art gallery as well as Grape. But what Henry really wanted was a band he could cultivate himself. When he saw Fraternity at Headquarters he knew he’d found what he was looking for. He made them an offer: he’d set them up in Adelaide, house them, equip them, manage them, pay them a wage.

It was, of course, an offer Fraternity couldn’t refuse. They left Adelaide set to return for good in January. On December 19, Vince broke the news in Go-Set that Fraternity were about to take the radical step of moving to Adelaide. That talk was still of going to America by following June or July.

It was going to Adelaide, removing themselves from the centre of things, that cruelled Fraternity’s potential. Such however, was the naivety and the conceit that characterised the times, Fraternity were convinced the world would come to them, and in the process establish Adelaide as an alternative music centre like some sort of antipodean Nashville.

It wouldn’t quite happen that way. Adelaide is a sleepy small town; not a city, many say, but a big country town, if a very sophisticated one. As Australia’s first tree settlement – as opposed to all other major cities, which have convict roots – the South Australian capital has always regarded itself as a bastion of liberalism and the arts. Adelaide also has an extremely significant rock’n’roll tradition. As the city that in the sixties spawned The Masters’ Apprentices and the Twilights and in the seventies spawned Cold Chisel, the Angels and the Little River Band, it has proved a well-spring of talent. But the Adelaide bands have always had to flee Adelaide to make it.

Fraternity flew in the face of convention when they were lured back to Adelaide. They were immediately elevated to superstar status there, and it was this that blinded them to reality. But then, in the early seventies, really was a concept seriously under siege.

The band played the Odyssey festival outside Sydney, between Christmas and New Year before heading for Adelaide where it would play Myponga, which would serve as a virtual homecoming. Neither Myponga nor Odyssey was the first Australian outdoor rock festival – that distinction belongs to Ourimbah – but they all predated Sunbury, which inaugurated in 1972, is the Oz rock festival most commonly remembered.

Allowing six months for the idea of Woodstock to reach Australia, Ourimbah was still premature. While its bill boasted the cream of Australia’s progressive bands, virtually none of them actually had a record out. A year later, when Myponga took place, it was a different story. 1971 can still be considered a golden era for Australian rock’n’roll, a time when it came of age in so many ways. By the early part of ’71, with at least a couple of the major record companies now confident enough to get down among the grass roots, a new wave of credible, creative post- San Francisco Australian bands dominated the music scene at every level. Having worked their way up on the live circuit, bands like Billy Thorpe’s born-again Aztecs, Spectrum, Chain, Blackfeather and Daddy Cool – nearly all of them from Melbourne – straddled the singles and newly-instituted albums charts alike, and filled houses all over the country.

.jpg) The timing was apposite. Australia in general was on the eve of something of a social revolution. After more than 20 years’ conservative liberal government, the Labor Party would storm to power in 1972, led by the reformist Gough Whitlam. With a bill boasting an exclusive appearance by Black Sabbath as well as the cream of Australia’s progressive bands, Myponga – bankrolled, almost inevitably, by Hamish Henry – was the biggest thing to hit Adelaide since the Beattles attracted a record crowd of 300.000 to a civic reception there in 1964.

The timing was apposite. Australia in general was on the eve of something of a social revolution. After more than 20 years’ conservative liberal government, the Labor Party would storm to power in 1972, led by the reformist Gough Whitlam. With a bill boasting an exclusive appearance by Black Sabbath as well as the cream of Australia’s progressive bands, Myponga – bankrolled, almost inevitably, by Hamish Henry – was the biggest thing to hit Adelaide since the Beattles attracted a record crowd of 300.000 to a civic reception there in 1964.

The act that epitomised the era was Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs. After Thorpie was declared bankrupt in 1967, he repaired to Melbourne to start over. By 1969, he had assembled a new incarnation of the Aztecs, featuring guitar hero Lobby Loyde. Thus commenced an ascent which would see Thorpie reign unassailably as the king of Oz rock during the early seventies, and with his trademark massive stacks of Strauss amplifiers he came pretty close. Former Valentine Wyn was a rougher, boozier sort of thing. The start of headbanging. The audience didn’t so much want to listen to the music as to be flattened by it.”

Fraternity had more than a little in common with both the blues and arty strains, but they were in no position to capitalise on it, stuck away in Adelaide, seemingly reluctant to get out on the road, and tied to a record company whose reach was severely limited.

After playing Myponga, the band went into the studio to put down Seasons of Change, the first single featuring Bon. On April 8, they played a support spot on the Adelaide leg of the Deep Purple / Free / Manfred Mann Chapter III Australian tour. At the end of April, as the single was released, they moved en masse onto the farm up in the hills.

It was perhaps the first sign of things to come when Seasons of Change was beaten to the punch nationally by the version released by Blackfeather, whose John Robinson was the song’s author after all. But Adelaide was an idyll which lulled Fraternity into a false sense of superiority, and as their Seasons of Change climbed the South Australian charts, they chose to deny the signs. ‘Fraternity live like no other band in Australia,” Vince wrote in Go-Set, “in house in the hills 17 Miles from Adelaide. Surrounded by seven acres of bushland, they’re secluded from everything but nature. What a buzz!” Fraternity had noted the Band’s example – the Band set up a communal base on a Woodstock farm called Big Pink – and Hemming’s Farm, as Fraternity’s Aldgate property was known, became their own Big Pink.

It was perhaps the first sign of things to come when Seasons of Change was beaten to the punch nationally by the version released by Blackfeather, whose John Robinson was the song’s author after all. But Adelaide was an idyll which lulled Fraternity into a false sense of superiority, and as their Seasons of Change climbed the South Australian charts, they chose to deny the signs. ‘Fraternity live like no other band in Australia,” Vince wrote in Go-Set, “in house in the hills 17 Miles from Adelaide. Surrounded by seven acres of bushland, they’re secluded from everything but nature. What a buzz!” Fraternity had noted the Band’s example – the Band set up a communal base on a Woodstock farm called Big Pink – and Hemming’s Farm, as Fraternity’s Aldgate property was known, became their own Big Pink.

In May, Uncle (John Ayers) came to town with Copperwine and stayed behind. Bruce asked him to join Fraternity and he move straight onto Aldgate. “Fraternity are into a trip of their own,” Vince went on. “Sure they know they’re good. Why else are they playing music professionally? But they’ve passed the ego since years ago. They don’t need ego trips, because they see too many good things in life, and they don’t want to lose them.”

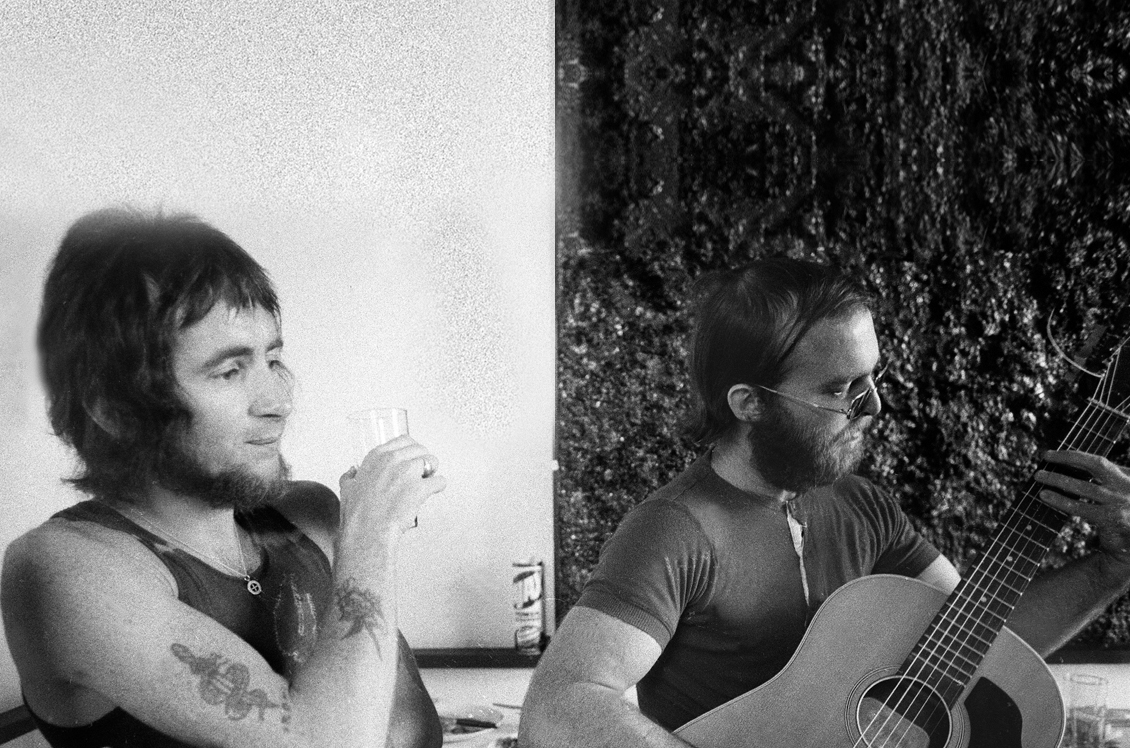

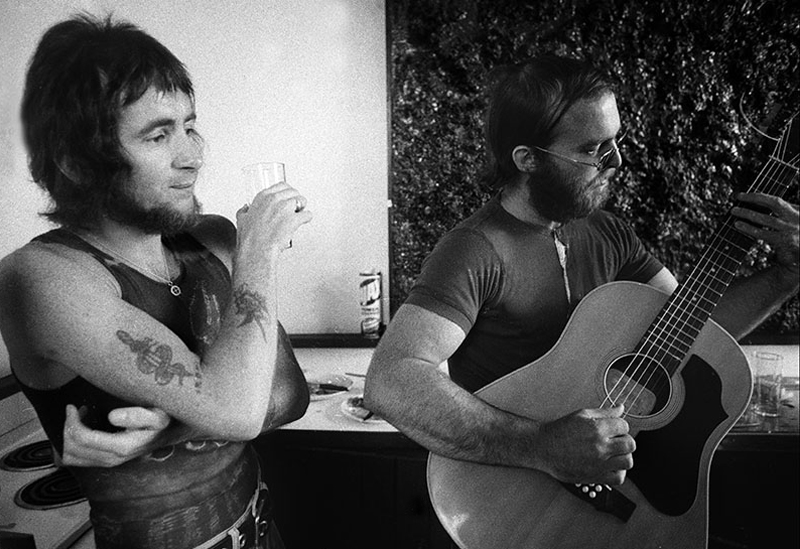

Of course, this idea was farcical as Fraternity was a strictly hierarchical, very volatile band. Bruce Howe was the boss – there were no two ways about that – and Mick Jurd was his senior partner. John Bisset, who wrote more material than any other single member of the band, was a brilliant but troubled man; he and Mick Jurd did not get on. Both Bon and Uncle simply managed to go with the flow. Uncle was out of it, even by the standards of the day.

Hamish Henry: “Bon was just a gregarious, very nice guy. I used to swim with him; he was a very good swimmer. To Bruce and Mick and John Bisset, a singer was probably something of a necessary evil, and so Bon revolved around them, rather than vice versa. Bon was always late, for rehearsals or gigs or whatever, and Bruce and Mick probably did discuss sacking him, but they couldn’t have done it. I think the band was appropriately named, because it was very much like a family, and Bon belonged to the family.” “Fraternity was a shitter for Bon, because all those other guys were educated, and he started to feel like he was inferior”, recalls Pat Pickett, who became friends with Bon after encountering Fraternity in Melbourne around the time. “They wouldn’t let him write any lyrics. A lot of early AC/DC stuff was written during those days.”

John Freeman: “Bon joined Fraternity to learn about music really, I think. Whatever else, he could sing, and he had what most singers would give their eyeteeth for – a distinctive voice. He joined Fraternity so he could learn about music, so he could go off and be a rock’n’roll star.”

Bon and Bruce were like chalk and cheese, but they shared a bond, and Bon readily deferred to Bruce. With his portly stature and prematurely thinning hair, Bruce looked almost Buddhistic, and indeed, he had a sort of aura about him, and a hold over the entire band. Bon and Bruce remained close even after Bon effectively deserted Fraternity. Bruce was perhaps the only man Bon ever confided in, whose advice Bon always sought out and respected. If Bon’s own musical input was less than it might have been, well, he felt privileged just to be working with musicians he held in awe. Not that a real lot of work can have been done. A couple of gigs a week, at most? In their entire three-year, two-album career, Fraternity produced barely a dozen original songs.

Bon and Bruce were like chalk and cheese, but they shared a bond, and Bon readily deferred to Bruce. With his portly stature and prematurely thinning hair, Bruce looked almost Buddhistic, and indeed, he had a sort of aura about him, and a hold over the entire band. Bon and Bruce remained close even after Bon effectively deserted Fraternity. Bruce was perhaps the only man Bon ever confided in, whose advice Bon always sought out and respected. If Bon’s own musical input was less than it might have been, well, he felt privileged just to be working with musicians he held in awe. Not that a real lot of work can have been done. A couple of gigs a week, at most? In their entire three-year, two-album career, Fraternity produced barely a dozen original songs.

Peter Head: “Fraternity spent most of their time on magic mushrooms. Everybody smoked dope, everybody. Everybody took mushrooms. Plus, Fraternity were all heavy drinkers as well’. The days and nights in Aldgate passed in one long, slow, lazy, hazy stoned-immaculate flow. If food was required, a big brown, sloppy pseudomacro stew was concocted. ‘Hamburgers hurt’, muttered Uncle. Every weekend, tribes of beautiful people from Adelaide would descend upon the place, tripping out, soaking up the good vibes generally, and fucking each other silly.

Bon was almost 25. He had not a care in the world. He acquired the nickname Ronnie Roadtest due to his willingness to try anything. Vince described him as ‘constantly in a dream world of his own… but he’s having a ball.’

Late in May, Fraternity went out on the road, first to Perth then to Queensland. Response in Perth was ecstatic – the band upstaged Chain, then riding high on the back of Black And blue – although in Queensland it was mixed. A Go-Set review of a Brisbane gig described them as “loud, too loud sometimes.” Sheer volume was part of Fraternity’s arrogance. This, of course, was a time when the Sunshine State’s fabled hillbilly dictator Joh Bjelke-Petersen was at the height of his powers, and Fraternity ran afoul of the law. Playing on the Gold Cost, the cops showed up and told them to turn down. Which they did, but with qualifications.

Late in May, Fraternity went out on the road, first to Perth then to Queensland. Response in Perth was ecstatic – the band upstaged Chain, then riding high on the back of Black And blue – although in Queensland it was mixed. A Go-Set review of a Brisbane gig described them as “loud, too loud sometimes.” Sheer volume was part of Fraternity’s arrogance. This, of course, was a time when the Sunshine State’s fabled hillbilly dictator Joh Bjelke-Petersen was at the height of his powers, and Fraternity ran afoul of the law. Playing on the Gold Cost, the cops showed up and told them to turn down. Which they did, but with qualifications.

Bruce Howe: “Bon made this speech, on stage, about the Queensland cops, you know, and the promoter was standing there, just shaking his head. Bon was quite naïve about political things. He was very street smart, he had this ability to assess people on the spot, their character, and generally his gut feelings were pretty good. But when it came to politics, that sort of knowledge, he was absolutely fucking hopeless.”

The band was now talking about going to America by June or July of the following year, 1972. Meantime, it’s not as if they put their heads down at all. It was summertime, and the living was easy.

Uncle: “There was this one party, the Three-Day Party, I think we’d played these two gigs, the Largs Pier, and the Bridgeway, there was 2.000 people there, it was Christmas or New Year’s Eve or something, and so everybody was invited up to our place for a party. It went for three days. There was barbeques, security guys, whole bars full of spirits, bonfires all round the lawn. I had children born in my bead and grandmothers die; I remember picking up my sheets with a broomstick and taking them out to the bonfire at the end of the three days, I wasn’t going to sleep in them again. I haven’t been to a three-day party since. Those days are gone.”

Hamish still believed and he put his money where his mouth was. When the band needed a new Hammond organ because this particular song called for that particular sound, he got it for them. He had the foresight to form a publishing company for the brand, so that they owned their own songs, which few bands do even today.

‘With hindsight, I’ve got a lot of respect for Hamish,” said Peter Head, who was also managed by him. “We used to rubbish him at the time, can him about being rich – we had no appreciation whatsoever of the value of money – but he was the one who made things possible.” As big fish in a small pond though, Fraternity were getting nowhere fast. Even Vince dared suggest they needed to ‘get off their arses and get some hard work done’.

Sam see: “Even though there was a sense that Fraternity shows were special, we were still doing the same gigs week in, week out. In those day the concept of making it had no reality at all.”

Sam see: “Even though there was a sense that Fraternity shows were special, we were still doing the same gigs week in, week out. In those day the concept of making it had no reality at all.”

By January, plans had changed again. The band was now going to go to England. This was yet another mistake – the wrong place to go, at the wrong time – but it was where Hamish had connections. In the past years, as he’d tried in vain to get both T Rex and Yes out to tour Australia, he’d at least made some contacts over there. The plan was to finally use free time at Armstrong’s, play a tour of South Australia, then leave.

The band spent a mere few days, again, in the studio, cutting the album which, in a fit of Australianness, would be called Flaming Galah. It proffered only three all-new songs – Welfare Boogie, Hemming’s Farm and Getting Off – next to rewritten and rerecorded versions of old material. Hamish set up a deal to release it through RCA.

The decision to leave was a bad one not only because the climate in England at that time wouldn’t suit a brand like Fraternity, but also because Australia itself was about to bound into the future. Merely weeks before Fraternity left, Billy Thorpe got the first remote mixing desk ever seen in the country. Of course, right then, Fraternity couldn’t went to get out of Australia.

Hamish: “We had this supreme self-confidence, and so coupled with a certain naivety, we couldn’t see any barriers whatsoever.”

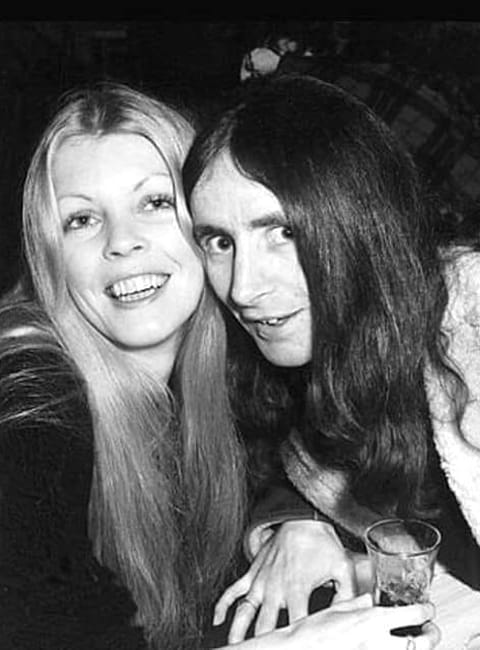

Prompted by the offer made by Hamish to pay for wives – not girlfriends – to go overseas with their husbands in the band. Bon and his girlfriend Irene decided to get married. They’d known each other a few scant months. Any ideas of a honeymoon that either Bon or Irene may have harboured were waylaid in excited anticipation of going to England. Besides which, the band was due to hit the road on February 12, on a tour devised by the Arts Council to take a bit of urban rock culture to the bush. Trucking through South Australia in a big black bus, Fraternity were their own merry pranksters. Bon, Ronnie Roadtest, was in the fine form, even if he was away from his new bride- or maybe because of it.

Prompted by the offer made by Hamish to pay for wives – not girlfriends – to go overseas with their husbands in the band. Bon and his girlfriend Irene decided to get married. They’d known each other a few scant months. Any ideas of a honeymoon that either Bon or Irene may have harboured were waylaid in excited anticipation of going to England. Besides which, the band was due to hit the road on February 12, on a tour devised by the Arts Council to take a bit of urban rock culture to the bush. Trucking through South Australia in a big black bus, Fraternity were their own merry pranksters. Bon, Ronnie Roadtest, was in the fine form, even if he was away from his new bride- or maybe because of it.

Back in Adelaide by early March, the band played two prom concerts as part of the Adelaide Festival of Arts program, another first for rock music in the State. Repeating a role created by Tully in Sydney, Fraternity accompanied singer Jeannie Lewis and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in a performance of Australian composer Peter Sculthorpe’s Love 2.000. It was a last gasp of the band’s ‘classical’ aspirations. It was not, by all reports, a pleasurable experience.

Welfare Boogie was released as a single later in the month. It did nothing, save perhaps provide a glimpse of the sort of themes Bon would later explore more fully.

I’ve got me a problem, a real social problem

I can’t find employment for more than a week

You might think I’m sleazy, but you know it ain’t easy

Finding employment’s job for a freak

The album followed in April. But the general attitude to Fraternity seemed to be they’d frittered their potential. By then though, the band was in England – not so much a band as a juggernaut, an entourage numbering 16 people and a bus, plus Clutch the dog of course! As far as Australia was concerned, Fraternity would be heard from no more. All the unfulfilled promises would be forgotten the name Fraternity would just fade away.

England in 1972 was teetering giddily on the stack-heels of glam rock. The glittering stars were T Rex, David Bowie, Gary Glitter, and the Sweet. Fraternity were a bunch of bearded wonders playing what was more than once described as ‘country rock’. It was all they could do to polish their R.M. Williams boots.

Fraternity’s 18 months in England would do nothing but grind the band down and finally out. The experience also claimed a heavy personal cost, as interpersonal relationships, including Bon and Irene’s marriage, soured. For the first six months they were there, they did next to nothing. They found a place to live – a big four-storey house in Finchley – and sat around waiting for something to happen.

Had they gone to America as originally planned, they might have fared better, as the music scene allowed for arrived for greater variations. But from the moment Fraternity arrived in London, it was obvious it wasn’t going to be the picnic they expected. The mountain of gear they’d hauled half way round the planet was already antiquated.

Hamish Henry set up shop, with partner, former DJ Tony MacArthur, as the Mainstreet Gramophone Company. MacArthur was managing French crooner Charles Aznavour, and acting for Dutch artrock band Focus. Hamish got Fraternity on the books with a powerful agency, MAM, but he had little to sell the band on. That they were almost the next big band in Australia wasn’t enough.

With more than a dozen people living under the same roof in Finchley, it was inevitable that friction would occur. The girls all had to go out and look for work to support the boys. Everyone was feeling the strain. England was cold and grey. Fraternity were nobodies there, and they were broke. Sparks started to fly. The only consolation the band found in England was the price of hash. They smoked blocks of red Leb by the brick. In November, they played their inaugural English gig at the Speakeasy. It was a non-event. Beyond that, all the band really had on the agenda was a short German tour. At least it got the boys out of the house.

With more than a dozen people living under the same roof in Finchley, it was inevitable that friction would occur. The girls all had to go out and look for work to support the boys. Everyone was feeling the strain. England was cold and grey. Fraternity were nobodies there, and they were broke. Sparks started to fly. The only consolation the band found in England was the price of hash. They smoked blocks of red Leb by the brick. In November, they played their inaugural English gig at the Speakeasy. It was a non-event. Beyond that, all the band really had on the agenda was a short German tour. At least it got the boys out of the house.

John Freeman wrote home to the News, “We are now moving into top gear in a flat-out bid to gain the necessary exposure that is vital for a new group such as ours.” That flat-out bid consisted of infrequent gigging – the most Hamish could hustle – playing supports with the bands that were second division at best – Atomic Rooster, Sparks, the Pink Fairies, Mungo Jerry. The most impressive bill Fraternity shared was with Fairport Convention.

Sam See: “It really was a very squalid house, full of people who weren’t united in anything except the music. I mean, the different personalities in that band I don’t think I’ve ever played in a band that was so diverse. And so when the music dropped off, all these personality differences came out. There was all sorts of cross-pollinations, violence both physical and verbal, mostly verbal.”

Bon didn’t know what to do with himself. He became frustrated when he was denied the release of performance. Without it, his whole being – he feared – was thrown into question. Hamish Henry: “The essence of Bon was when he was on stage, his thumbs stuck in his jeans and his chest sticking out, strutting his stuff. That was all he ever wanted to do.”

Bon was reduced to getting a day job, like the girls. He went to work in a factory where he knotted wigs. He got Sam a job there too. Fraternity scored only the odd gig. They’d had the wind knocked out their sails. Sam See remembers one of the last gigs he played with the band. “We were all in the bus, the juggernaut, rolling down to Bournmouth to support Status Quo. The only thing we knew about them then was Pictures Of Matchstick Men; it would’ve been just before they broke again with Piledriver.

This was probably the last sign of the Fraternity arrogance which I always loved. As usual, on the way to the gig, we’re having a few drinks, we reckon we’re gonna cream ‘em. So we’re sitting there on the bus outside the Bournmouth Odeon, waiting for the hall to open, because we were egalitarian, we all used to help lug the gear in. No stardom for us – bullshit! These two Bentleys pull up, and these guys resplendent in Kings Road finery get out. We’re there, you know, ‘Look at these pooftas,” Bon’s going ‘Yaarrrgh!’ We’re at this point extremely confident we’re going to make a name for ourselves. So we went on, we did quite well, didn’t get an encore, but did okay, and then Status Quo came on, and they’d changed out of their satin and bells into the familiar Status Quo jeans and T-shirts, and they were three times as loud as us and twice as polished. They were hot. “We lurched back to London with our tails between our legs. It was probably one of those nights where someone had too much to drink and punched somebody else, I can’t remember for sure. But something went wrong within the ego of the band definitely. By the time winter rolled around, I’d had it.”

This was probably the last sign of the Fraternity arrogance which I always loved. As usual, on the way to the gig, we’re having a few drinks, we reckon we’re gonna cream ‘em. So we’re sitting there on the bus outside the Bournmouth Odeon, waiting for the hall to open, because we were egalitarian, we all used to help lug the gear in. No stardom for us – bullshit! These two Bentleys pull up, and these guys resplendent in Kings Road finery get out. We’re there, you know, ‘Look at these pooftas,” Bon’s going ‘Yaarrrgh!’ We’re at this point extremely confident we’re going to make a name for ourselves. So we went on, we did quite well, didn’t get an encore, but did okay, and then Status Quo came on, and they’d changed out of their satin and bells into the familiar Status Quo jeans and T-shirts, and they were three times as loud as us and twice as polished. They were hot. “We lurched back to London with our tails between our legs. It was probably one of those nights where someone had too much to drink and punched somebody else, I can’t remember for sure. But something went wrong within the ego of the band definitely. By the time winter rolled around, I’d had it.”

Some time early in the new year Fraternity changed their name to Fang, “to fit with the current English trend,” whatever they thought that was. To Hamish, this marked the real beginning of the end. In April, Fang played a couple of gigs with Geordie, the Novocastrian band which, ironically contained Brian Johnson, the singer who would eventually replace Bon in AC/DC. Graem, Bon’s younger brother, visited England at that time, and remembers those shows. Brian used to carry his guitar player on his shoulders.

I think that’s where Ron got the idea, because when he joined AC/DC there was no one around doing that sort of thing. Angus was the perfect guy to carry around. He was so small. In May, the band played a short tour of provinces with Kraut-rock doomsayers, Amon Duul. The headliners, the Gloucestershire Echo said, were “an enormous contrast to the Australian band who started the concert (whose) unambitious but multi-decibel bedecked set sounded much like the rhythm and blues material that was churned out by a million would-be Rolling Stones in the early 60’s.”

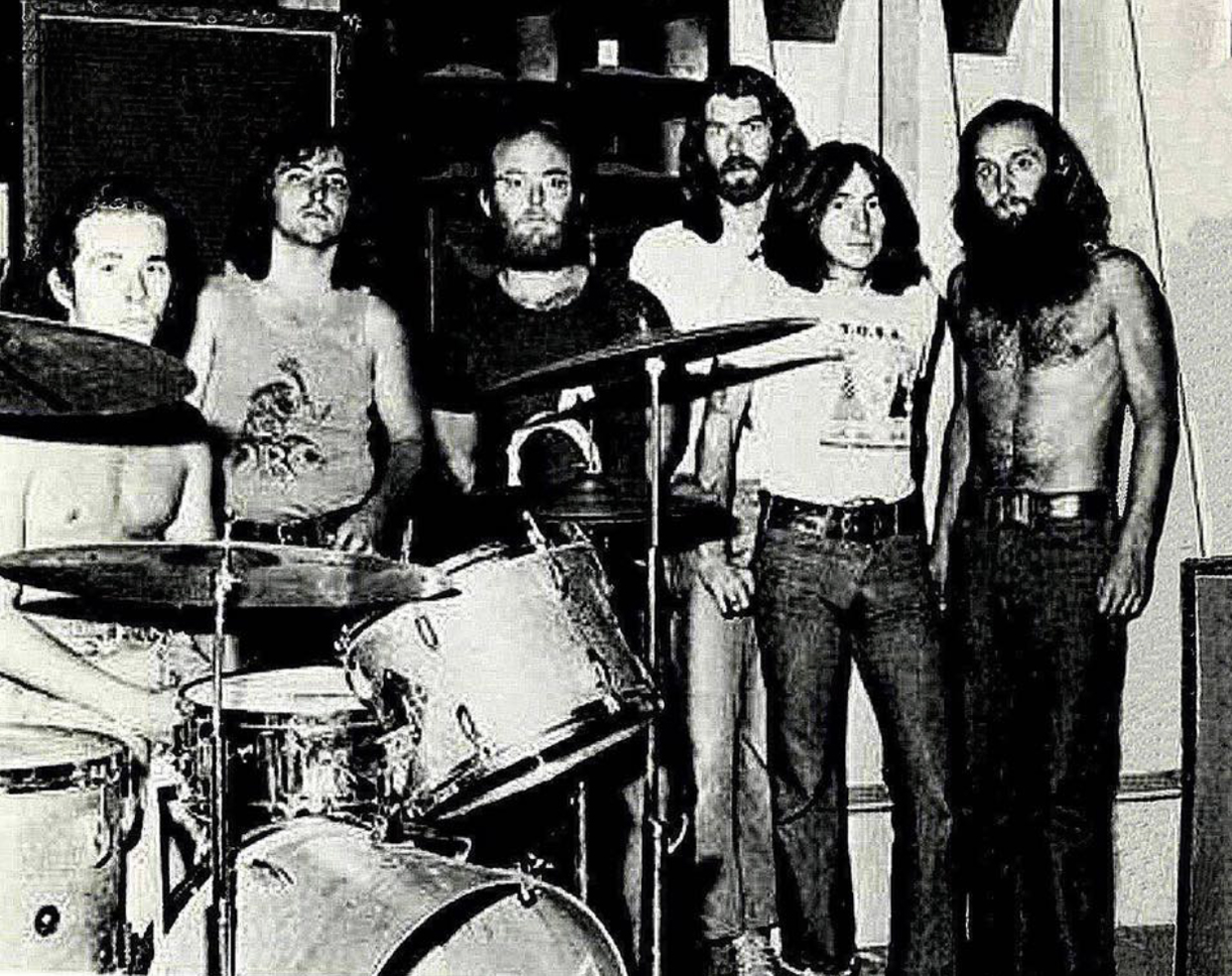

Relations within the band and its extended family were deteriorating to the point that final implosion was imminent. Uncle hocked Vicki’s Mixmaster to buy hash. The drinking became increasingly heavy, putting a surly spin on things. By the English summer of ’73 the band had ceased paying rent. In August it played what would be its last ever gig, a two-bit festival at Windsor. Hamish bailed out. He’d had enough. He’d sunk a small fortune into Fraternity, and he could no longer see any prospect of a return.

The dream was over. “I think the real reason Fraternity failed in England was because they were just too loud,” he says now. The band lingered in London, shell-shocked just wondering what to do. Bon got a job in a nearby pub, behind the bar. Not surprisingly, he was natural.

Finally back in Adelaide, Fraternity were in suspension, licking their wounds. Bon felt loyalties strongly, but even he wasn’t sure that Fraternity, as such, had a future. He had to go out and get a job. No one else was going to support him, and it might keep him out of trouble. So, like Bruce who was supporting his young family, by working as a builder’s labourer, Bon started a full-time day job for the first time in almost ten years. He loaded trucks at the Wallaroo fertilizer plant. It was a monumental comedown, but it was what he had to do to stay afloat. Bon could be stoic about such things.

He got a bike, a big Triumph, to get around on. He was mucking around with Peter Head’s Mount Lofty Rangers, a band, of sorts, which at least allowed him to keep its hands in. It was one night after he’d had a row with Irene that he arrived, already drunk, at a Rangers rehearsal. And then, stormed off from there, even more drunk, to ride his bike at high speed into an oncoming car. He was almost killed and was in a coma for three days.

He got a bike, a big Triumph, to get around on. He was mucking around with Peter Head’s Mount Lofty Rangers, a band, of sorts, which at least allowed him to keep its hands in. It was one night after he’d had a row with Irene that he arrived, already drunk, at a Rangers rehearsal. And then, stormed off from there, even more drunk, to ride his bike at high speed into an oncoming car. He was almost killed and was in a coma for three days.

But it wasn’t long before he was back on his feet, if unsteadily. He was already anxious about his professional future. Irene recalls: “We went to a concert, I can’t remember who it was, it was an outdoor concert, and there were people there from the industry who just walked right past him, and he said something like, ‘here arseholes used to be all over me.’ He thought he was just a has-been.

For want of any other option, Bon joined in rehearsals with Bruce, Uncle, John Freeman and guitarist Mauri Berg, formerly of Headband. Mick Jurd, like John Bisset, has remained in England. But Bon wasn’t entirely convinced. When the News devoted a story to Fratenity’s ostensible reformation, it started to smell suspiciously like the bad old days. The band came across a full of all the same old bullshit: “We’ve got a lot of plans, and we’re in no hurry.”

The last thing Bon wanted was a repeat performance of the last three wasted years. He had to find a ticket out. It would be AC/DC.

- Liner notes extracted from the essential Clinton Walker book Highway To Hell – The Life & Times of AC/DC Legend Bon Scott. (Sun, Australia. Sidgwick & Jackson, U.K)

- Album conceived and compiled by Glenn A. Baker, Peter Shillito and Kevin Mueller. Issued by arrangement with Hamish Henry and the Dolphin Music Group. Special thanks to Clinton Walker, David Jay, Jimmy Stewart, Denis Whitburn, Ian McFarlane and Bob King.

- Mastered by Warren Barnett at the Raven Lab. Sonic Solution process (on certain tracks) by Daniel Segal at Sony.